As more professional sports leagues begin to delve deeper into the issue of concussions and traumatic brain injuries, a trickle-down effect is taking place, and the prevalence of concussions in youth sports has resulted in increased scrutiny. The underlying fear is that the risks inherent in youth athletics outweigh the positives of participation – fitness, teamwork, discipline, mental fortitude, etc. The debate is primarily focused on football, but concussions can occur during any type of strenuous activity, whether it be hockey or high jumping. Regardless of your personal stance on this issue, one thing is clear: young athletes put themselves at risk every time they step on the field, court, ice, or track.

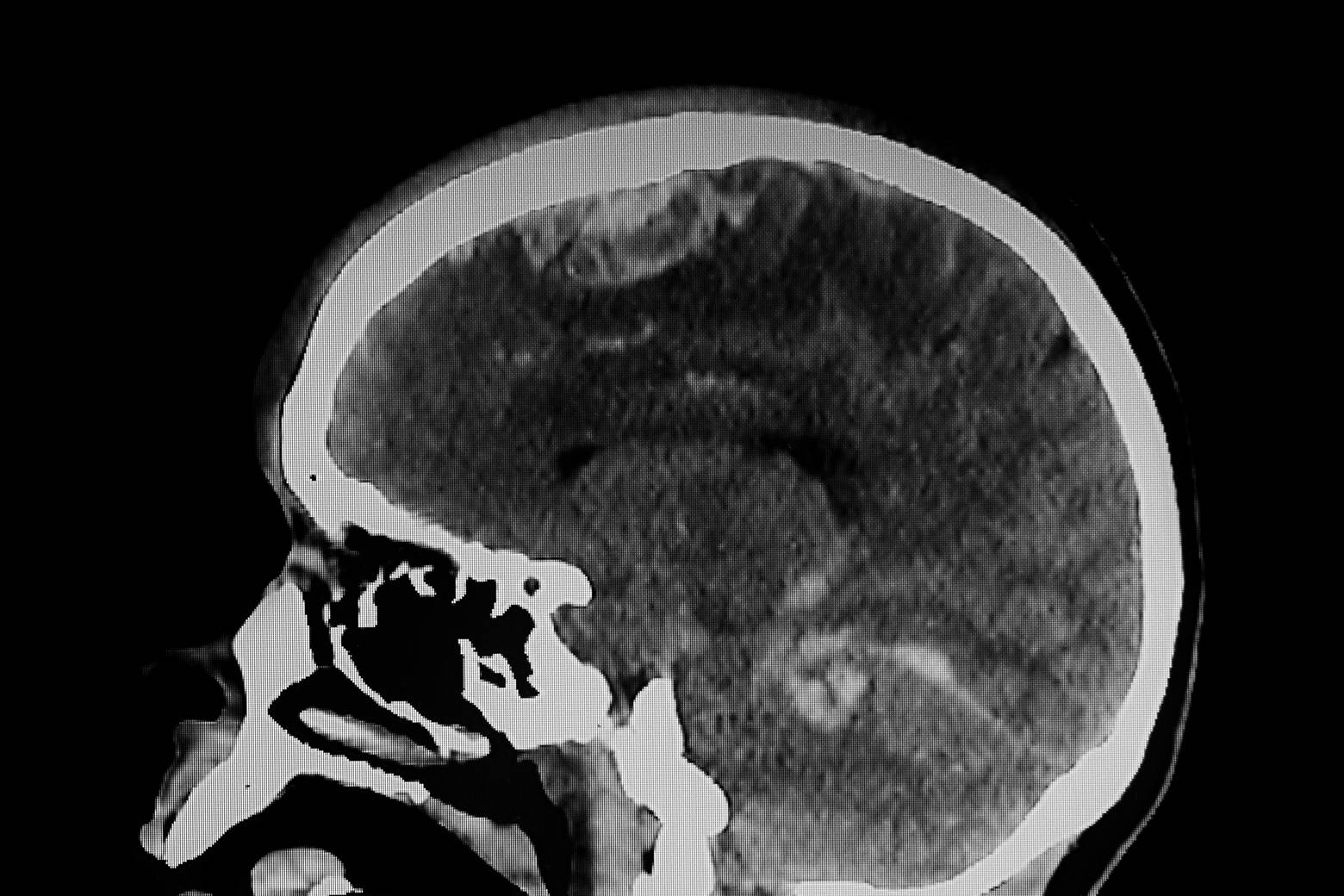

Concussions (also known as mild traumatic brain injury – or MTBI) are the result of blows to the head that cause the brain to collide with the interior walls of the skull. Symptoms include dizziness, headache, nausea, and memory loss, among many others. Many times, symptoms of a concussion are minimal, vague, and/or non-descript, resulting in numerous unreported and undiagnosed incidents. This is especially troublesome since undiagnosed or repeated concussions can lead to additional brain injuries and can cause serious long-term physical, mental, and emotional effects, including permanent disability or even death.

The majority of sports-related youth concussions are the result of severe collisions sustained during football-related activities; for example, approximately 47% of high school football players are diagnosed with concussions each season, and the majority of those occur on the practice field rather than during games. Furthermore, a report released in October by the National Academy of Sciences found that high school football players are twice as likely to suffer a concussion than those competing in college. In all, seven high-school athletes died in 2013 as a result of football-related injuries. As a result, there has been a significant decline in youth football participation in recent years, with reports naming concussions as the primary reason for the drop off.

To help combat the injuries while still keeping competition vibrant, some states are now requiring high school athletic leagues to furnish coaches, officials, players, and parents with literature regarding concussions and the health impact of sustaining more than one brain injury. Minnesota law now requires coaches and officials to participate in online training to recognize the signs and symptoms of concussions. In California, new legislation has gone into effect limiting the amount of contact in school-sponsored football. Youth teams in that state are now limited to full-contact practices that do not exceed 90 minutes and that are only held twice a week; no contact practices can be held during the off-season. Texas has also recently implemented similar restrictions so that teams are now only allowed 90 minutes of full-contact practice per week.

New technology is also being developed to mitigate the risks of concussions. For instance, newly-developed helmets are equipped with sensors to provide coaches and trainers with immediate feedback after collisions. This should allow coaches to make more informed decisions about players’ health status and inform the medical and training staff about necessary actions to take in the event of a concussion. While these helmets represent significant progress toward the diagnosis and treatment of MTBI, they cannot altogether eliminate the potential for concussion. At this point, nothing can.

Awareness and vigilance at all levels of athletics should help prevent and diagnose concussions in the future, leading to a healthier players. But sports will always remain intrinsically violent, and concussions and other injuries will remain inevitable. If you or your child has been involved in a violent collision that could potentially have resulted in a concussion, tell the medical and coaching staff immediately. Be sure to follow your institution’s protocol and consult your physician as soon as possible.

References:

Conway, T. (2013, November 14). High school football player Chad Stover passes away following head injury. Bleacher Report. Retrieved from http://bleacherreport.com/articles/1851069-hs-football-player-chad-stover-passes-away-following-head-injury

Dugan, S., Seymour, L., Roesler, J., Glover, L., & Kinde, M. (2014, September). This is your brain on sports: Measuring concussions in high school athletes in the Twin Cities metropolitan area. Cinical and Health Affairs. Retrieved from http://www.minnesotamedicine.com/Portals/mnmed/September%202014/Clinical_ThisIsYourBrainOnSports_1409.pdf

Gregory, S. (2014, September 18). The tragic risk of American football. TIME. Retrieved from http://time.com/3397085/the-tragic-risks-of-american-football/?pcd=hp-magmod